What is the definition of Ekklesia?

The following is an extract from his book, and this has to be the best description I have ever read. If you are frustrated with how we “do church”, then his Book is a must read.

I love highlighting and writing comments as I read a book and my copy of his book has highlighted sections and comments on almost every page.

In fact we will be incorporating this book as a mandatory read for everyone who joins our ®Growing Deep and Strong movement. The book is full of proven results on how to transform and disciple a nation.

But, back to the question,

What is the definition of Ekklesia?

Read on, you will be richer for the experience.

At the time of Jesus’ birth and all through His life on earth, there were three main institutions in Israel,

- The Temple,

- The synagogue

- And the Ekklesia.

It is usually assumed that all three were religious bodies, but only the Temple and the synagogue fit that description.

The ekklesia was not religious at all, since it was first developed as a ruling assembly of citizens in the Grecian democracy to govern its city-states. It consisted of men eighteen years or older who had done two years of military service; in essence, people substantially committed to their city-state.

In a broader sense, ekklesia also came to mean an assembly of citizens duly convened. When the more hierarchical Romans replaced the Greeks in the imperial scene, the Romans assimilated the concept. Consequently, the general public in Jesus’ day understood ekklesia to mean both the secular institution and the governmental system it represented.

We find an example of the Hellenistic ekklesia in the book of Acts, when Paul’s associates Gaius and Aristarchus were dragged to the theater in Ephesus (a Roman colony) in response to a complaint brought by the local union of silversmiths.

The word that is translated assembly in this instance is the same one rendered church elsewhere in the New Testament (see Acts 19:32, 39). Here ekklesia refers to the crowd twice, and a third time to the court itself, showing that the term was employed to describe a body of people assembled to conduct governmental business.

In fact, when the town clerk “dismissed the assembly [ekklesia]” amidst warnings of illegality (Acts 19:41), the same noun translated assembly in that verse is translated church 112 times elsewhere in the New Testament.

This assembly model is precisely the one that Jesus chose to emulate conceptually, as we will see in greater detail later.

It is most revealing that Jesus did not say, “I will build My Temple” or “I will build My synagogue” -the two premier Jewish religious institutions. If He were thinking along those lines, He could have said, “I will restore and even surpass the former glory of the Temple so that heads of state will journey to Jerusalem, as the Queen of Sheba did, until every world ruler has bent his or her knee before the God worshiped here.”

He could have also said, “I will build My own worldwide network of synagogues to make the Gospel available to people in every nation.” The synagogue was the religious place where Jews met on the sabbath to read the Scriptures and to pray. Like the Temple, a building was essential to the synagogue’s function.

When the moment came to introduce His transformational agency, Jesus selected neither one. Instead, He announced that He would build His Ekklesia choosing a term that, in the Roman Empire in general and also in subjugated Israel, described a governmental institution.

The Lord did not discard everything that went on in the Temple or the synagogue but assimilated significant components from both institutions into His Ekklesia.

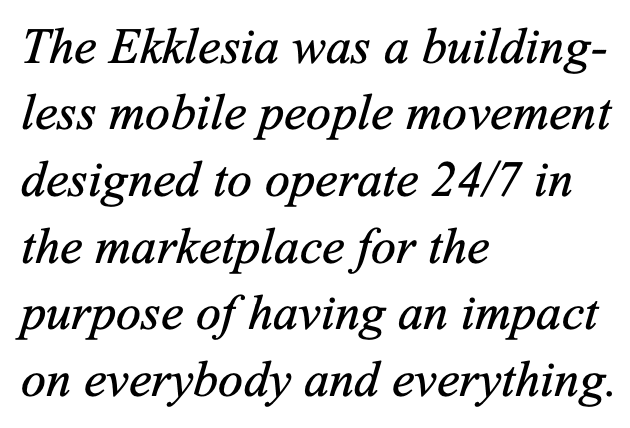

Where the Temple and the synagogue differ with Jesus’ Ekklesia, however, is in the areas of constitution, location, and mobility.

The Temple and the synagogue were static institutions that functioned in buildings that members had to go to on specified occasions, whereas the Ekklesia was a building-less mobile people movement designed to operate 24/7 in the marketplace for the purpose of having an impact on everybody and everything.

The Conventus: A Fascinating Caveat

The Greek and Roman versions of the ekklesia appeared in different forms and sizes, all of which are relevant to the subject at hand. But one format is especially notable: the Conventus Civium Romanorum, Or convents for short.

According to Sir William Ramsay, when a group of Roman citizens as small as two or three gathered anywhere in the world, it constituted the conventus as a local expression of Rome.

Even though geography separated them from the capital of the empire and the emperor, their coming together as fellow citizens automatically brought the power and presence of Rome into their midst. This was indeed the Roman ekklesia in a microcosm.

We see an expression of this in Acts 16, when the Roman magistrates panicked at the realization that they had beaten and thrown in prison a fellow citizen (Paul) without the due process accorded to Romans.

Later on, another centurion and his commander exhibited similar concerns after finding out that Paul, who they were about to punish, was also a Roman citizen (see Acts 22:24-29). Evidently, when two or more Roman citizens connected, the laws (and protection) of the emperor were in their midst.

Jesus made His authority available to His Ekklesia in the same manner, but in a much greater dimension when He stipulated that “whatever you bind on earth shall have been bound in heaven; and whatever you loose on earth shall have been loosed in heaven” (Matthew 18:18, emphasis added).

By selecting the ekklesia model over the Temple or the synagogue, Jesus chose an agency better suited to succeed everywhere not just in Israel, where He ministered extensively, but also in the pagan societies where He would send His disciples.

His ultimate objective was not to reproduce or expand religious institutions. It was to see nations discipled by inserting the leaven of His Kingdom into their social fiber through His Ekklesia.

Once we understand that Jesus chose a concept with which His disciples and their contemporaries were already familiar in the secular arena, we can then see why He taught so few times about it:

There was no need to explain what everybody already knew. It was unnecessary to teach the obvious. to the people in the Roman Empire, including Israel, the ekklesia was as familiar a concept as the state assembly is to those living in a democracy. or the management team is to the employees in a corporation.

There was no need for Jesus, or for the New Testament writers later on, to describe for their audiences what was already known as a decision-making, society-impacting people institution.

On the other hand, it was essential for Jesus to teach extensively about the Kingdom of God, or its equivalent, the Kingdom of heaven, as the new factor in the equation so much so that He made reference to the Kingdom over a hundred times.

Turning Tables into Pulpits

This is present in the first description of the assembly (Ekklesia) of His followers right after Pentecost, where they were seen “continually devoting themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to fellowship, to the breaking of bread [eating) and to prayer” (Acts 2:42, emphasis added).

This was not a one-time or sporadic occurrence, since one of the most common examples of a church meeting in the New Testament is believers partaking of food, to which the addition of the doctrine of the apostles to ascertain and to obey the will of God–upgraded it from a mere meal into an assembly.

Those mealtimes constituted an inclusive forum (unlike the Temple or the synagogue), thus inserting the Ekklesia into everyday secular life instead of isolating it from it.

By making the Ekklesia run on existing social tracks (mealtimes), Jesus turned tables into pulpits and homes into assembly halls into which strangers were welcome, rendering them prime candidates for evangelism.

No wonder His disciples’ archenemies accused them, just a few weeks after Pentecost, of having “filled Jerusalem with your doctrine” (Acts 5:28 NKIV).

This was so, not because all of Jerusalem was trying to attend a church service, but because the Ekklesia had thoroughly permeated the city, so much so that people lined up their sick on sidewalks, awaiting the shadow of Peter to heal them, something that turned Jerusalem into a citywide campus for the Ekklesia (see Acts 5:15-16).

This turned out to be the case – first, because Jesus did not confine the gathering of His followers to buildings or subject them to a rigid schedule of centralized meetings.

Instead, it was people who constituted His Ekklesia (wherever and whenever as few as two or three gathered, with His manifest presence in their midst).

And second, because Jesus’ Ekklesia was not meant to be a sterile, sanitized holding tank into which His disciples were to store in isolation converts fished out of a turbulent and doomed sea, to await the arrival of a refrigerator ship for transfer to a heavenly port for final processing.

Instead, His Ekklesia, whether in the embryonic expression of the conventus or in a more expansive version, was designed as the vehicle to inject the leaven of the Kingdom of God into the dough of society so that first people, and then cities and eventually nations, would be discipled (see Acts 1:8; 5:28; 19:10; Romans 15:22-24; Revelation 21:24-25).

At the heart of every cry for revival today, there is always a deep longing to find the way to the majestic, all-powerful Ekklesia that Jesus launched, free from any form of restraint or containment and overflowing with power.

Dr. Ed Silvoso, a best-selling author trained in both theology and business. He is widely recognized as a strategist and solid Bible teacher who specializes in nation and marketplace transformation. Initially trained in business, his background includes banking, hospital administration and financial services. He is the founder and president of Harvest evangelism ane leader of Transform Our World Network. You can find out more at https://www.transformourworld.org/ and Ed Silvoso.com.

Carl is a follower of Jesus Christ; Founder and Author of the Christian Discipleship and Leadership program called the Growing Deep and Strong® Series. He is also the Founder and Director of Find Your Destiny™.

His mandate is to be a catalyst and facilitator in developing people who will become leaders and disciplers of others and to create an environment that creates leaders that transform nations.